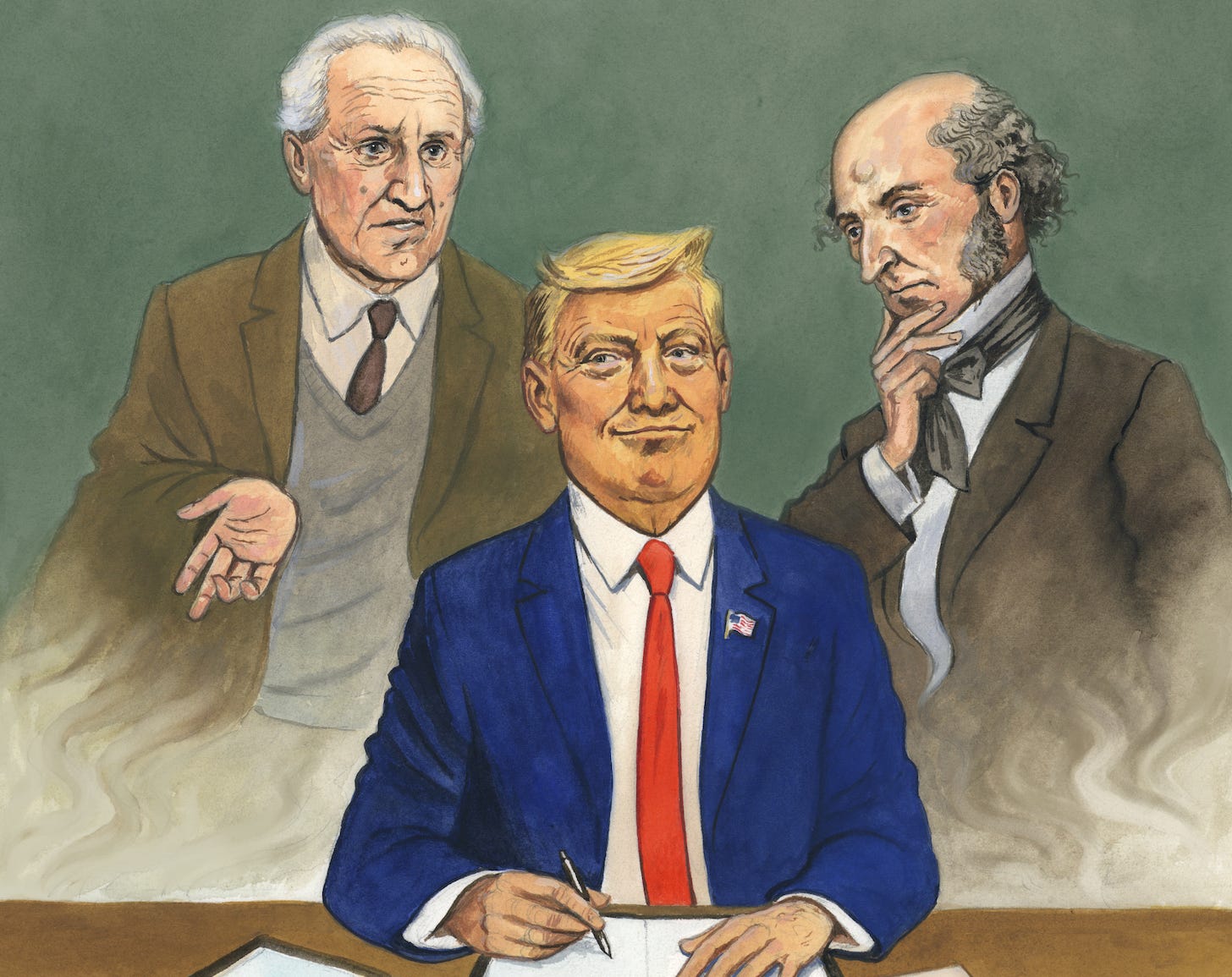

Editor’s note: For the latest issue of inquisitive, Heterodox Academy President John Tomasi contributed a think-piece on what John Stuart Mill and Herbert Marcuse can teach us about the Trump administration’s actions towards institutions of higher education in America. Here, I ask him some follow-up questions to unpack further the thinking behind the essay and what HxA is doing to meet the moment. - Alice Dreger, HxA’s Managing Editor

Alice Dreger: Your scholarship is in political philosophy, as evidenced by the approach you bring to this essay. How do you understand the role of philosophy in social reform work generally and in the educational reform work of Heterodox Academy (HxA) in particular?

John Tomasi: As a discipline, philosophy sits atop a paradox: philosophy is at once the strangest of things but also the most ordinary. Philosophy is strange because it takes seriously odd questions like, “How do we know anything? Or, “What is the nature of being?” Or, “How should people live together?” And when I say “takes seriously,” I mean that, over the decades, centuries, and millennia since these questions were first posed, philosophers have written books and articles numbering in the hundreds, thousands, and hundreds of thousands exploring questions like these. No doubt philosophers will go on working on these strange questions – perhaps forever.

And yet philosophy is simultaneously the most familiar of disciplines, since philosophy defines and clarifies the concepts and paradigms by which we understand the world. In this, philosophy is a peculiarly intimate discipline, since it addresses and seeks to improve the very most personal of activities, namely, the thinking that goes on silently in each of our heads.

In our effort to improve the academy, HxA has always sought first to understand it. Founded in 2015 by social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, sociologist Chris Martin, and legal scholar Nicholas Rosenkranz, HxA soon drew the attention of historians, economists, sociologists, lawyers, and brilliant scholars from many more fields. In the decade since the founding, these affiliated scholars have built up an impressive body of work to help us better understand the state of open inquiry on our college campuses and to understand what reforms might make the ideal of open inquiry a more fully lived reality. HxA scholars have found ways to measure the state of open inquiry, to put contemporary campus conflicts in historical context, to connect campus events to wider social trends, to analyze the impact of various policies on open inquiry, and much more.

Within this melange of disciplinary efforts, philosophy also has a role to play: it is that strange but intimate role I mentioned, to clarify concepts in the hope of improving our thinking.

Alice: You note in your inquisitive essay that “Marcuse says ‘free speech’ reproduces inequalities in social and cultural power.” This is a counterintuitive claim. Can you explain more what he means – maybe give some examples from the academy – and tell us what you think about this claim?

John: A great way to understand Marcuse’s point is by considering the mission of HxA. At HxA, we seek to equip our members and other campus leaders to foster open inquiry, on campus and across the academy as a whole. We think of open inquiry as a cultural condition with three characteristics: the free exchange of ideas, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement. Open inquiry is the combined presence and operation of these three values. Open inquiry allows the university to pursue its core mission, the pursuit and widening of human understanding.

But now let’s drop the Marcusean argument into this state of affairs. Imagine a campus that has formal protections for free speech and the broad exchange of ideas. The rules and practices on this campus protect students and professors in speaking freely: no one is punished for expressing their viewpoint, no matter how socially controversial the topic. But let’s imagine that on this campus, most everyone shares the same basic worldview. The moral, historical, and empirical assumptions about social life that are taken for granted by most everyone on this campus may be highly controversial among the citizens of the wider society of which this university is a part. But on the campus, people generally all vote the same way, read the news the same way, and identify causes of moral outrage (and civic pride) the same way. In short, this campus lacks viewpoint diversity.

It is not hard to imagine such a state of affairs. Indeed HxA was initially founded out of a concern that universities had increasingly become political and intellectual echo-chambers, precisely as a result of having become less intellectually diverse. One simple way to measure this is through political ideology. In the 1960s, the American professoriate leaned left to right in a ratio of about 2:1. But soon this ratio began to widen. Between 1989 and 2017, ratios of liberal to conservative faculty roughly more than doubled, to 5:1. Today, some estimates put the overall ratio at 17:1, with an even wider ratio among junior professors.

In Marcusian terms, a large and growing imbalance of viewpoint diversity denotes a large and growing imbalance of power. If we have formal free speech protections and yet most or all of the authority figures think and reason from a single parochial set of premises, the exchange of ideas on that campus is likely simply to reproduce the assumptions of the speakers – whether or not they are true. Unless this preexisting imbalance of power is recognized and addressed, Marcuse might say, formal principles of toleration and free speech will in practice be repressive. In HxA terminology, unless we have viewpoint diversity on our campuses, the cultural condition of open inquiry can be achieved only in weak and attenuated form, if it can be achieved at all

Alice: One of the surprising (even startling) turns in your essay is where you suggest that some of the actions of the Trump administration are “deeply Marcusean in spirit.” As you know, Trump is on the right – some might say far right – and Marcuse was on the far left. How do you see the administration’s actions towards universities as “Marcusean”?

John: There are many ways to read Marcuse. And readers especially diverge when it comes to understanding Marcuse’s positive recommendation for social reform. As I just noted, I read Marcuse as making a structural point: liberal norms of free expression and the toleration of differing opinions are unlikely to perform their social roles if the preexisting structures of power are badly imbalanced. But confronted with such a state of affairs, what is to be done?

In Repressive Tolerance, Marcuse suggests some muscular responses. As you note, Marcuse is writing from the far left, and he describes American society in the 1960s as having a severe imbalance of power toward the political right. According to Marcuse, free thinking becomes ever less possible as power becomes ever more unequal. Toleration and free speech become repressive in conditions of unbalanced power because, instead of liberating minds, they operate to solidify and reinforce the status quo. This is why Marcuse calls for the “cancellation of the liberal creed of free and equal discussion” (106). If some find this undemocratic, Marcuse disagrees: “The problem is not that of an educational dictatorship, but that of breaking the tyranny of the closed society” (106).

If you read some of the Trump-aligned thinkers who write about higher education, you can see surprising parallels to this Marcusian approach to social reform. A notable example is Max Eden’s December 6, 2024, essay “A Comprehensive Guide to Overhauling Higher Education.” In that essay, Eden provides a remarkable roadmap of higher education policies and executive orders that the Trump administration has in fact pursued in the opening months of his presidency. For example, regarding Linda McMahon, former WWE executive and President-elect Trump’s Secretary of Education, Eden wrote: “To scare universities straight, McMahon should start by taking a prize scalp. She should simply destroy Columbia University.” In its opening salvo, it seemed, the Trump administration set out to do just that. Crucially, Eden observes, many of the muscular actions that he recommends would not require congressional approval: President Trump could accomplish these goals directly by a series of Executive Orders.

What could possibly justify such extreme and apparently anti-democratic recommendations? Here is where Marcuse comes back in. These actions are justified, Eden argues, in order to “make campus speech free again.” By allowing themselves to drift into a condition of ever greater ideological homogeneity, universities have effectively become what Marcuse called “closed societies.” Such societies are “closed,” Marcuse tells us, because they “serve to enclose the mind within the established universe and discourse.” Whether knowingly or not, these systems have become sites of indoctrination, not free learning. It is no affront to democracy, from this Marcusean perspective, to employ unusual (and possibly even extra-legal) measures to break the tyranny of these closed systems. The government takes one “scalp” in order to free millions of minds.

Thus, as I explain in my essay, we see in the Trump administration some eerie echoes of Marcusian ideas.

Alice: You close your essay by suggesting that John Stuart Mill still offers us wisdom on how to manage campus life. You write, “Rather than withdrawing toleration from perceived enemies, we extend toleration in a principled way — much as Mill recommended.” How do you see HxA leading in this approach on campuses?

John: Mill was a great defender of free speech and toleration, essential elements of the liberal creed. Our university system today is besieged by actors who, for diverse and sometimes opposing reasons, seek the cancellation of that creed.

On the one hand, since Marcuse wrote in the late 1960s, there has been a movement within some corners of the academy that is skeptical of open inquiry, seeing the free exchange of ideas as a tool used by the powerful to reinforce their privilege. Cancel culture, and the rush of many campus leaders to embrace DEI, may well be remembered as the high points of that tide of campus intolerance.

More recently, and putatively in response to that movement, we are now seeing a movement from large segments of the public, and from the government officials who represent them, that likewise rejects these liberal ideas of toleration but for ideologically opposite reasons. Without naming Marcuse, and likely without even being aware of Marcusian analysis, thinkers such as Max Eden and policy makers within the Trump administration have been pursuing new policies of intolerance themselves. They often claim to be enacting these policies in the name of reforming our universities. Yet their reforms are consistently marked by curious, and worrying, fascination with “taking scalps.”

At HxA, we defend the principles of open inquiry against critics and opponents from every direction. We see the university as a special type of convening. Rather than a battleground where opposing groups clash in zero-sum contests, we see our universities as communities of imperfect learners. At its best, the university is a convening that accepts, and celebrates, the unending capacity of all its participants – students and scholars alike – to learn more from each other. Rather than a closed society, we seek a more open society.

But at HxA, our methods say as much about us as our goals. HxA is a membership organization of campus insiders. As insiders, we believe that we ourselves have special powers and special responsibilities to help foster the campus cultures of open inquiry we seek. A basic feature of the liberal creed is what is sometimes called the doctrine of meliorism. This is the belief that, rather than fomenting a revolution or joining in a campaign of righteous destruction, people can work together across lines of difference, using reason and persuasion as the central tools for building a better world. HxA is working hard to build that better world on our campuses. We hope you will join us in this great adventure.