When Students Want Professors Fired for Political Beliefs

Crunching data from the Knight Foundation provides additional insights.

Political speech has long been a contentious issue on college campuses, and it’s only gotten worse. In recent years, professors have been disciplined, suspended, and even terminated from their positions for speech that others considered offensive.

Many of these actions against faculty are initiated by student complaints. So, what do we know about students’ views of how professors’ politics should be handled?

In 2024, the Knight Foundation surveyed a representative sample of almost 1,700 American undergraduate students to assess their views on free expression in higher education. One issue that was measured but that did not appear in Knight’s final report caught my eye.

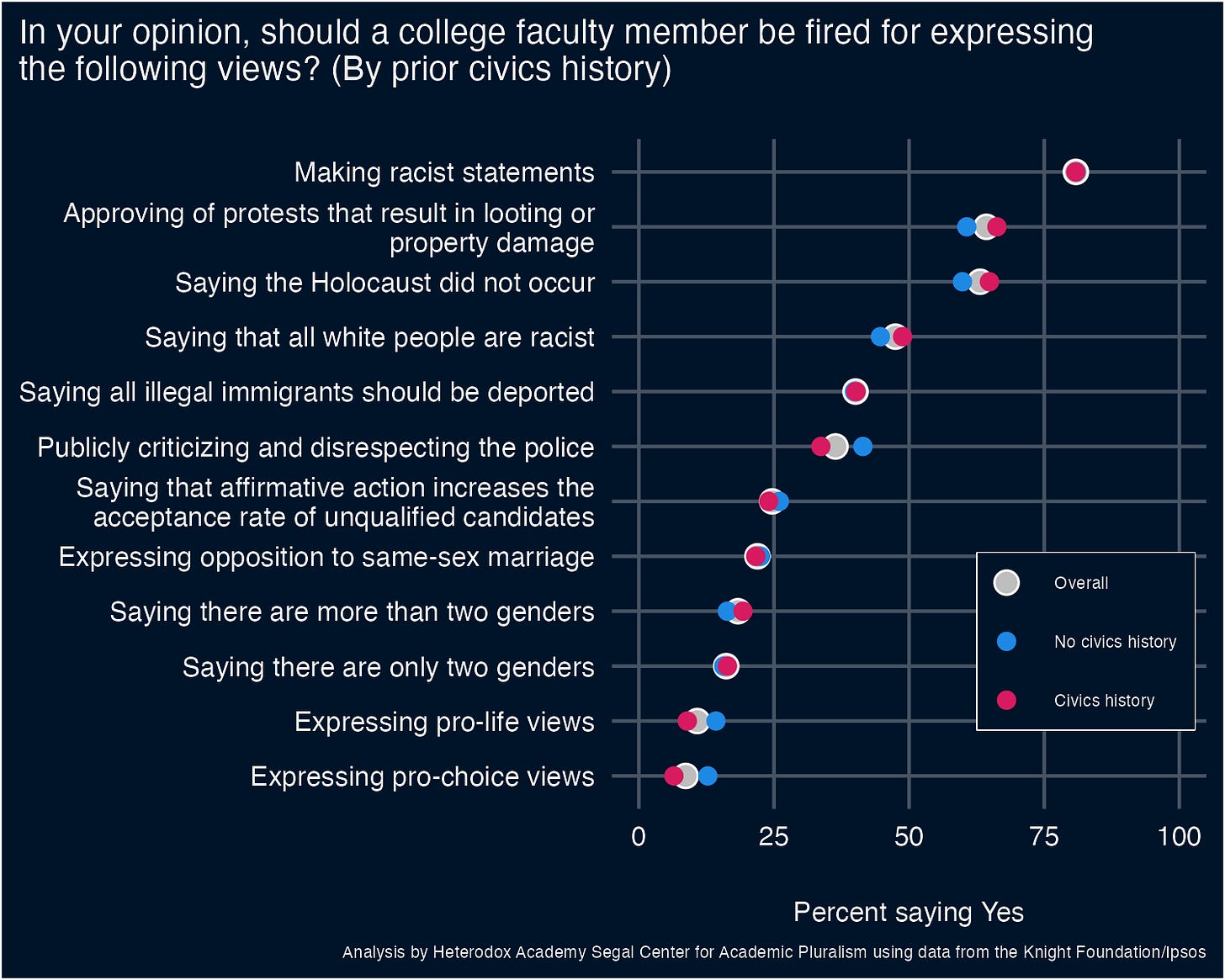

For a list of twelve controversial views, students were asked whether they think a college faculty member should be fired for expressing them. The views covered a lot of ground — touching on issues of immigration, racism, gender, and abortion — and included a roughly equal mix of views that typically offend the left and those that offend the right.

I became curious: Who among these students was more likely to endorse firing faculty members for controversial speech, and when?

There’s a stereotype that liberal college students are more censorious, so one might predict that most of the heat would come from that side of the aisle. Indeed, surveys do tend to find that members of that group are more likely than conservative college students to believe that words can be harmful — at least in the abstract.

That did turn out to be true of the students surveyed by Knight as well: 29% of Democratic students reported thinking that the First Amendment “goes too far” in the protections it guarantees compared to 19% of Republican students. And when asked whether “some forms of speech can be as damaging as physical violence to the recipient,” 83% of Democratic students agreed, compared to 59% of Republican students.

Another metric suggested striking similarity between Democrats and Republicans: 90% of Democrats and 94% of Republicans said that freedom of speech was “very” or “extremely” important to them. With such broad apparent agreement on the value of free speech, one might expect nearly everyone in this sample to shudder at the thought of firing a faculty member over their speech.

But if I have learned anything as a researcher, it is that what people tell you about their beliefs in the abstract can have little to do with their response to a specific situation. This dataset had measures of both, which makes it valuable for identifying the more powerful driver of censorship among students.

I started exploring this data by simply looking at the percentage of students in the sample who endorsed firing a faculty member over each view.

Right away, it was clear that there was a lot of variability in students’ responses across controversial views. A few views were considered by the majority of students to warrant termination, including saying the Holocaust did not occur (63.3%), approving of protests that result in looting or property damage (64.3%), and making racist statements (80.9%). Others were widely considered to be within the realm of acceptable speech, including pro-choice and pro-life views on abortion (considered a fireable offense by only 8-10% of students) and views on the gender binary (16-18%).

Next, I broke responses down along a few dimensions I thought could be relevant: student political affiliation (Democrats, Republicans, Independents, and Others), whether students had ever taken a First-Amendment-focused civics class (respondents were asked, “Have you ever taken classes in high school or college that dealt with the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution?”), and whether students reported thinking that First Amendment protections go too far. The results came out like this:

Notice first, the partisan gaps (especially those between Democrats and Republicans) were generally large, although not always in the same direction. Unsurprisingly and consistent with a large literature on political bias, Democrats were more punitive toward views that seemed offensive to liberals (for example, saying all illegal immigrants should be deported), while Republicans were more punitive of views that seemed offensive to conservatives (for example, publicly criticizing and disrespecting the police).

What is really surprising is how little difference there was between students who said they did and did not have prior First Amendment education. In fact, students who indicated having had prior civics education on the First Amendment appeared no less likely to endorse firing faculty members for expressing political views than students who didn’t.

The largest difference appeared on the question of publicly criticizing the police, where 36% of those with prior civics education and 41% without it endorsed firing a professor expressing that view. Not too surprisingly, believing that the First Amendment goes too far in its protections was linked with more punitive responses for most of the views.

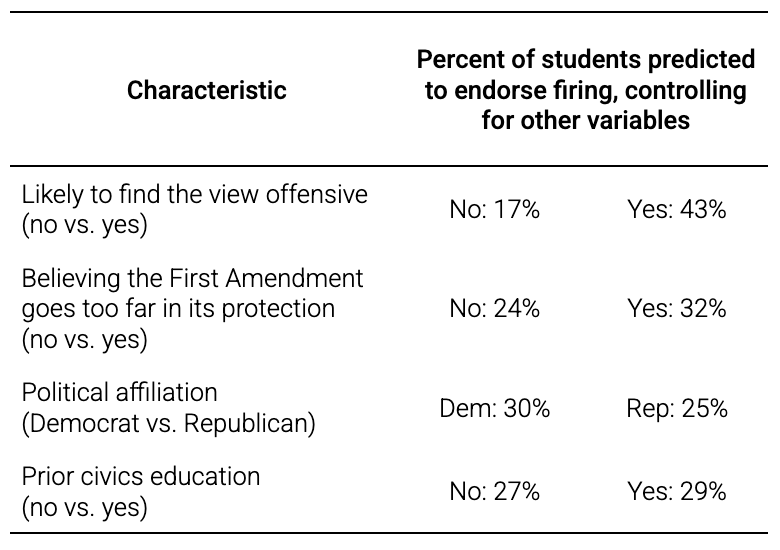

Next, I wanted to see more generally how each of these factors related to students’ censorship tendencies. I used multilevel logistic regression, which models the relationship between a number of predictor variables and a dichotomous (yes/no) outcome — in this case, whether students thought a faculty member should be fired for expressing a given view.

Given the political nature of the views, and the fact that Independents tended to fall close to the sample average, I limited the analyses to the Democrats and Republicans in the sample. Based on existing data on Americans’ reactions to offensive speech, I created a variable to reflect whether the view being evaluated was likely to offend the respondent based on that party affiliation. This resulted in seven views that were likely to offend Democrats and five that were likely to offend Republicans (summarized in the table below).

For the average student in the sample, I could now examine how their party affiliation, distaste for particular views, prior civics education, and beliefs about the First Amendment related to their likelihood of saying that a faculty member should be fired for any given view. Using the model, I could then predict the probability that a student with different characteristics (e.g., Democrat vs. Republican; civics education or no) would endorse firing a faculty member over their speech.

According to this model, the strongest predictor of students’ censorship tendencies was whether they were likely (vs. not likely) to be offended by the view: students who were likely to be offended were 26% more likely to endorse faculty dismissal for speech than those who were not (p < .001).

Students who believed that the First Amendment goes too far in its protection were 8% more likely to endorse firing faculty over their speech (p = .004).

After controlling for these variables, interestingly, Democrat vs. Republican party affiliation and civics education appeared statistically unrelated to students’ propensity to call for professors to be fired (ps of .074 and .300, respectively).

The table below summarizes the predicted percentage of students who would want a faculty member fired for their speech, broken down by characteristic.

So what did we learn?

The initial descriptive statistics suggested that, while some views were widely considered unacceptable (the most egregious being “making racist statements”), views on other controversial topics like gender and abortion did not elicit from students a desire to see a faculty member fired, regardless of which position they supported. Why students recognize room for tolerating disagreement on some hot-button issues but not others could be an interesting topic for researchers to pursue in the future, in part because we might learn how to convert potential cancellations into opportunities for constructive dialogue.

In my statistical modeling, the most powerful predictor of students’ responses about whether they would want a professor fired was the mismatch between the professor’s view and their own political perspective. By contrast, left-right political orientation played a relatively miniscule role in whether students were censorious, and those who said they had received formal education about the First Amendment — which in theory should increase students’ tolerance for opposing views — were no less punitive.

These results echo many others from the literature on political psychology: tolerating disagreeable ideas is challenging for people of all political stripes. In the context of higher education, where we at HxA believe students should be learning how to engage with difficult ideas — not to suppress them — there seems to be room for improvement.